PMA Highlights: William Pope.L's Maybe

Referring to himself as “a fisherman of social absurdity,” conceptual and performance artist William Pope.L challenges us to confront some of the most pressing questions about American society as well as about the very nature of art over the last four decades.

His boundary-breaking practice ranges from performance to painting, installation, video, sculpture, and theater.

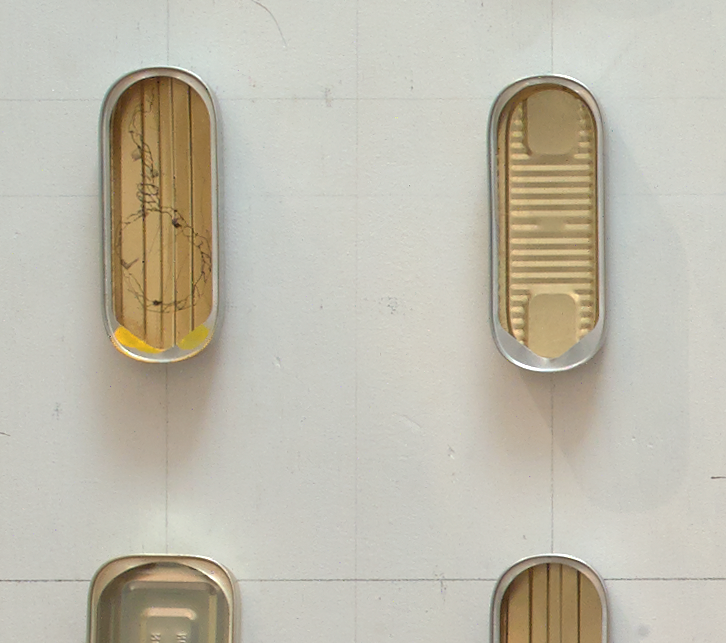

William Pope.L (United States, born 1955), Maybe, 2009-2010, MDF board, sardine cans, plastic bag, cardboard box, nails, electrical extension cord, paint, graphite, 96 x 96 x 18 inches, Gift of Alex Fisher, 2010.13, Image courtesy Luc Demers

By Jessica May, Deputy Director and Robert and Elizabeth Nanovic Chief Curator

Pope.L is renowned for using his own body to make art that expands traditional boundaries of medium and subject matter, and brings gender, class and racial stereotypes uncomfortably close to the artist and his audiences. Pope.L’s work explores the fraught connection between prosperity and what he calls “have-not-ness.”

Pope.L, whose name integrates his father’s surname with the first letter of his mother’s maiden name, Lancaster, creates artwork that has a strong element of time, through his performances or—in many cases—their residue. From 1990 to 2010, Pope.L was a lecturer of Theater and Rhetoric at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. He currently serves on the faculty of the Department of Visual Arts at the University of Chicago. The traveling retrospective called William Pope.L: eRacism captured national headlines when the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) rescinded its grant award in 2002; coincidentally, it was organized by PMA’s Director Mark Bessire, then Director at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art, Sarah Kellner at Diverse Works Art Space in Houston, Texas, and Stuart Horodner at Portland Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA), Oregon. In fall 2019, a trio of exhibitions of his work, collectively titled Instigation, Aspiration, Perspiration, were on view at The Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Public Art Fund in New York. Organized by the Public Art Fund, Pope.L and over 140 volunteer participants crawled the streets and parks of Downtown Manhattan in the collective public performance, Conquest.

Maybe of 2009–10 recalls the act of eating as well as the former sardine industry, yet leaves open the basic question whether this process is a pleasurable part of everyday life, a deliberately uncomfortable ritual, or lack of consumption altogether. Although the work is based on Pope.L’s physical experience, Maybe is not the residual document of a public performance. Instead, it is not unlike a modern abstract painting, with a large-scale backing board that meets the floor and secures to a wall. Glued to the backdrop of the work is a near-perfect grid of empty sardine cans, the contents eaten by Pope.L. The empty cans also serve as a reminder about inequalities of food access in the United States, and specifically in Maine are a visual cue about the closure of last U.S. cannery in Prospect Harbor in 2010. Yet the grid is incomplete, and assorted materials in front of the work—including loose, empty cans and an ordinary orange electrical cord—suggest the kinds of equipment from an artist’s studio that one rarely sees in an art museum. Maybe thus creates bridges between everyday life and making art, between the formal space of the museum, the wild, messy, imaginative space of the studio, and the artist’s own body. We are invited to move back in time, from the artist’s consumption of sardines, one can at a time, through the conception and planning of a work of art, to the museum staff, carefully installing objects meant to recall the exciting haze of discovery.

In recent conversation with Pope.L, he alerted the museum to an overlooked yet significant detail of the piece. The artist recalled, “I believe in some of the cans I drew images of nooses—their inclusion sort of thicken the ‘lightness’ of the work and darken it a bit—and move it toward Christian symbolism, lynching, trash psychology—a simple cheap container becomes a crucible for loss—whether it be a fishing industry, or a people or the son of god or faith.” The PMA apologizes to the artist for not looking closer at the work in our collection. He is right.