The Real, Long Journey: Dan Crewe and the Joy of Serendipity

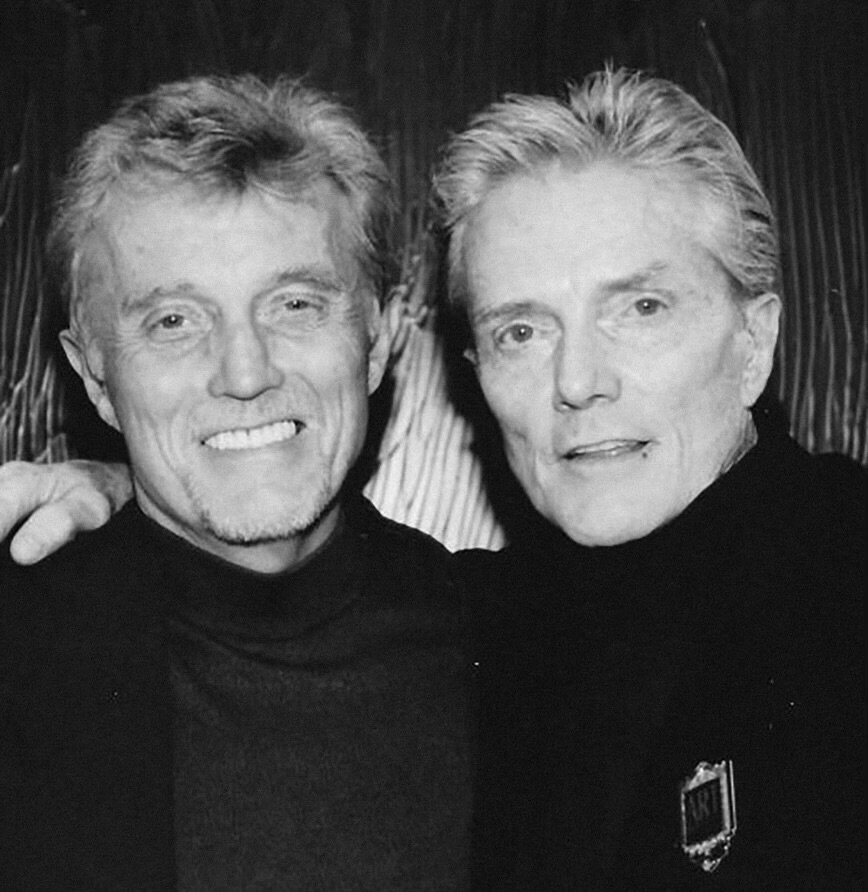

Dan and Bob Crewe. Photo provided by Dan Crewe.

Dan Crewe didn’t plan for any of this. An avid bicyclist, Crewe understands that you can end up at a remarkable destination simply by following the path forward, and continuing to move forward he has. That’s how he ended up in Maine for good, figuratively and literally, back in 1991. After a summer spent in North Haven, away from the Connecticut home he shared with his [now former] wife, Cindy [now Cidney], Crewe recalls, “I came home from my bike ride one morning, and I said to Cindy, ‘I don't know what this means, but I'm not going back!’” And with that, everything changed. Shortly after settling in Maine, Crewe partnered with friend Bob Ludwig to cofound Gateway Mastering Studios in Portland. Oddly, Gateway—an internationally renowned leader in music—was not Crewe’s most significant relationship with an internationally renowned leader in music, nor even with a man named Bob.

The Bob Crewe Generation, 1966. Photo by: Otto Fenn. Photo courtesy of the Bob Crewe Foundation.

Dan’s older brother, Bob Crewe, began writing chart-topping hits in the 1950s. Over the next several decades, the brothers Crewe built an incredibly successful music empire with Bob the creative lead and Dan helming the business side of things. Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, Lesley Gore, and many more artists were catapulted to fame and fortune due to the success of the Crewes, and in the ”anything goes” era of midcentury music, Dan’s steady handling of the partnership enabled the duo to thrive. As with many rock and roll narratives, however, fast-living and excess were a constant in Bob’s life, and Dan eventually stepped away from the business and his brother to pursue other interests. Years later, as sobriety and time eased disagreements and provided perspective, they came together once again to establish the Bob Crewe Foundation, for which Dan is the President and Chairman. Funded primarily through royalties, the foundation provides grants to a wide array of arts organizations as well as organizations that support LGBTQ projects and initiatives.

Crewe’s sexuality, and the evolution of coming to terms with it and ultimately championing it, is a vital part of the organization’s values. As a young man and United States Naval Academy graduate, Crewe felt conflicted, “being gay [and] having to live in the shadows, having to be constantly feeling the sense of duality, living in an era of condemnation and rejection.” Balancing that duality of being—on one hand, feared and literal rejection, while also having the option to remain silent—deeply informed the impact Crewe wanted to make, years later, through the foundation. “Of course,” he notes, “part of my being in that ‘class of criticized’ makes you more sensitive to the plight of others, especially those, in my case, [in which] nobody had to know if I wanted to remain silent. . . . I became more sensitized to those who could not avoid their social injustice.”

Jeffrey Gibson (United States, born 1972), PEOPLE LIKE US, 2018, glass and plastic beads, tin, copper and gold-finished jingles, artificial sinew, quartz crystal, silver-coated copper wire, druzy crystal, nylon thread, nylon fringe, acrylic felt, acrylic paint, repurposed wool blanket, recycled jersey stuffing, rawhide, 60 1/2 x 24 1/2 x 14 inches. Gift of Crewe Foundation and Family, 2019.13. Image courtesy Peter Mauney. © Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles, California

Art and music, of course, have long been avenues for addressing inequities and sparking social change. The throughlines between social justice and the arts inform the work of the Crewe Foundation, but also how Dan enjoys his personal time, namely collecting artwork. The desire to be an art collector began for Crewe while he was still an officer in the military, though he acknowledges he could not afford it at the time. “I think my salary at that point was around $6,000 a year,” he recalls. “I saw a Noguchi piece of furniture. Not the glass versions, but the original wood versions. It was $150. That sounds ridiculously cheap, but in 1958, $150 with a salary of $6,000 . . . I could not justify it. [But] it was the first time I realized I wanted to acquire something because I just love looking at it.”

The convergence of attraction, social justice, and happenstance was certainly the case in 2018, when on a PMA trip to Art Basel, Crewe fell for an artwork that he wanted to purchase just for the love of it. “First of all, I absolutely did not intend to buy any art,” Crewe laughs. “It was not in the cards.” But something about Jeffrey Gibson’s PEOPLE LIKE US captured his attention—and heart—and he continued to think about it for hours after first seeing it. “All the elements of what motivates action were there,” he continues. “’People like us’—that’s it! Like, that's the word. I looked at it, and being a gay man myself, my first reaction was, ‘Oh, people like me.’ I asked Jeffrey what he meant by it eventually, and he said it means both things. It means people do like us, but also, people like us.” It was that moment of serendipity (“I wouldn't have been able to write this script”) that led Crewe to purchase the artwork, but it was his commitment to the arts and social justice that immediately led him toward something larger, community-focused, and impactful. Almost immediately upon purchasing the piece, Crewe chose to donate the artwork to the Portland Museum of Art. The artwork has since become a visitor favorite and a highlight of the museum’s contemporary art collection.

“All the elements of what motivates action were there. ’People like us’—that’s it! Like, that’s the word. I looked at it, and being a gay man myself, my first reaction was, ‘Oh, people like me.’”

Over time, as his career began to take shape in the 1960s through today, Crewe’s motivations around art never changed. “I think art collecting is the primary focus of, ‘I see what I like, I buy what I can,’” he shares. “Art has always been important. It has a value—there is an exchange value. But the intent of acquisition has never been predicated on its value.”

Jessie Bullens-Crewe, Cindy Crewe, Reid Crewe, Dan Crewe, and Bob Crewe. Photo courtesy of Bob Crewe.

Crewe talks a lot about serendipity in his life, specifically with regard to his philanthropy. The Crewe Foundation was created alongside, and then in memory of, his brother, and many highlights of a life can be traced to moments of chance. Chance cuts both ways, Crewe concedes, underscoring that when it comes to being philanthropic, “I probably wouldn't be if it hadn't been for the death of my youngest daughter when she was 11.”

When Crewe and his ex-wife moved to Maine from Connecticut, they did so with their two daughters, nine and six years old. Their motivation, like many, was an idyllic setting in which to raise their children—the region’s more humanistic, simpler way of life was in stark contrast to their New York-adjacent lives in Connecticut. However, only a few years into their time in Maine, their daughter, Jessie Bullens-Crewe, died from fourth-stage Hodgkin’s disease at the age of 11.

Photo courtesy of Dan Crewe.

“Everything changed through that horrible experience,” Crewe says. Over time, the depths of pain and sadness began to motivate Crewe and redirect his energies, with lasting and meaningful effect. Crewe credits the loss of his daughter as a turning point and “the ignition of my philanthropy.” He started a foundation that would raise funds for the Maine Children’s Cancer Program—with contributions that would go to cancer research and support for families and caretakers. He has supported the PMA, Maine College of Art and Design, the University of Maine, and many other organizations. “The big thing is now,” he shares, “[I] live my life to make a difference wherever I can, at the level I can. That's what I attempt to do.”

Now 87 years old, Dan Crewe connects the chapters of his life through a string of serendipitous moments. From his early days in the military to helping make Maine a better place, it’s all connected by happenstance and fortuity. “It all makes sense,” he illuminates. “Also funny, to get where you get and do something that you're doing, and then you suddenly realize, ‘Oh, this is all part of a real long journey.’” It’s a journey Crewe didn’t plan on taking, but he’s made the best of it along the way.